Introduction

A couple of years ago, I had the opportunity to join a robotics company. Initially, I didn’t know much about the field, but it quickly became a passion for me. The most exciting part was seeing how my programming could directly affect the real world, instead of just working with data on a screen. However, working with physical objects means you need to be very cautious. For instance, even a minor error in the code could potentially damage costly equipment like LiDAR sensors worth thousands of dollars. This is precisely why simulation is so integral to robotics. It not only helps in avoiding costly mistakes but also speeds up development, enables repeatable testing scenarios, and allows you to work without being physically next to the robots.

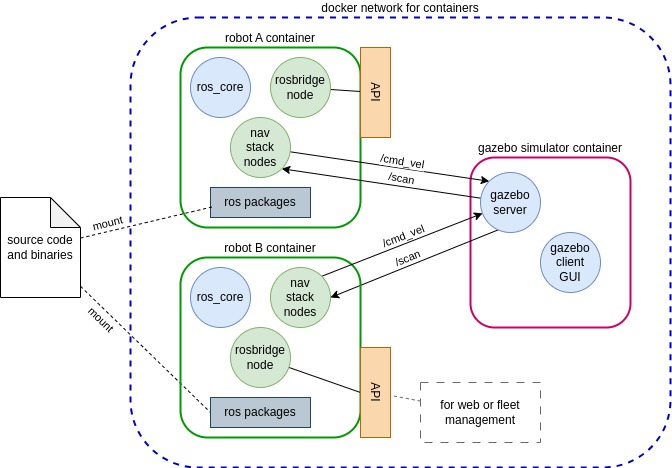

In this blog, I will focus on my project related to multi-robot simulation or fleet simulation using ROS and Gazebo simulator. While creating a simulation for a single Automated Mobile Robot (AMR) in ROS is straightforward with just a few configuration files, developing a simulation for multiple robots that can sense and interact with each other is a completely different challenge.

Defining the Problem

The core challenge in multi-robot simulation using ROS is the necessity for a single simulation server capable of managing multiple robots. This requirement diverges from the more common approach of simulating just one robot. The ROS packages designed for Gazebo simulations are predominantly tailored for this single-robot model, which means there’s a need to either modify these packages or find alternative solutions. To explain this in more detail, ROS uses gazebo_ros_pkgs, a collection of packages providing the essential interfaces for robot simulation in the Gazebo 3D environment.

This set includes, among others, the gazebo_ros package and gazebo_plugins. The gazebo_ros package primarily handles the spawning of URDF models into the Gazebo 3D environment through its factory topics. Meanwhile, gazebo_plugins comprises various Gazebo plugins loaded directly by Gazebo. In my project, I am particularly focused on plugins for differential drive and laser scanning.

Consequently, this approach requires spawning multiple robots and utilizing several identical plugins in Gazebo. Communication is conducted through topics, necessitating a system to differentiate among them, likely through the use of namespaces. Another implication is the need to operate with a single ros_master (the central ROS broker) for all robots. This setup, I anticipate, could lead to complexities. Additionally, a significant concern for me is the reliance on a single, centralized ros_master for all robots.

My Approach

Here are the key points that define my strategy for addressing this challenge:

- Uniformity Across Robots: Each robot must be identical in terms of source code and default configurations.

- Unique Identifiers: The only distinguishing factors between robots should be their names (possibly IP addresses) and initial positions.

- Internal Functionality Encapsulation: All internal functions should be encapsulated, hidden from external access, and only reachable through a well-defined API.

This doesn’t apply to data exchanged with Gazebo. - Individual ros_master for Each Robot: Every robot should operate its own ros_master.

- Single Gazebo Instance: There must be only one Gazebo instance serving all robots.

Uniform Codebase

For simplicity, I’ve opted for identical robots, which naturally implies identical code as well. This means that even topic names used for data transmission, such as /cmd_vel for controlling robot velocity, should be consistent across all robots. This approach avoids any potential name collisions, as the robots will not be aware of each other’s presence.

Docker containers provide an elegant solution in this context. Each container represents a robot and will mount the source code from a shared location. Moreover, this arrangement facilitates the mounting of build binaries, ensuring that any development carried out on one robot is seamlessly reflected across all containers.

Naming and Positioning

Each robot must have a unique identifier. In this case, it will be the Docker container name, doubling as the robot’s name. Docker’s ability to assign unique IP addresses within a local network aligns perfectly with real-world scenarios where multiple robots are connected to a Wi-Fi network, each with its own IP address.

For initial positioning, just like in the real world, robots need to start at different locations. This will be managed by a unique configuration file for each robot, specifying its spawn coordinates. This file could also save the robot’s current position, allowing it to respawn at the same location after a restart.

Backend Encapsulation

Using Docker containers is ideal for encapsulating the robot’s backend logic. The robot’s API, implemented as a message-passing mechanism, will be the only interface for external interaction. This API can be supported by rosbridge, allowing the robot to communicate with the outside world through a specific TCP/IP port. Messages are serialized as JSON and transmitted over WebSockets. Client-side communication can be handled by libraries like roslibjs for web apps or roslibpy for Python apps.

Individual ros_master

Having a separate ros_master for each robot simplifies namespace management and avoids the complexities of a single global ros_master.

Global Gazebo Simulation Server

Managing the Gazebo simulation server globally is arguably the most challenging aspect of this project. Gazebo is designed to run as a server, which is advantageous. Typically, it runs alongside ros_master and its nodes. However, in this scenario, Gazebo must operate in a separate Docker container with its own IP address, facilitating communication. A compelling aspect of this setup is the ability to run Gazebo on a completely different computer. This flexibility is crucial, especially since handling multiple robots can be CPU-intensive. Running Gazebo on a dedicated server is a viable option, though it might be affected by slower network speeds. For my project, I’ve chosen a simpler route, running everything on a single computer.

The critical aspect is establishing communication between each robot and the Gazebo simulation server. Typically, a robot is spawned in Gazebo using a .launch file where the spawn_model node from the gazebo_ros package is initiates. This node, taking URDF or SDF models as input, spawns them in the 3D environment. By default, this node communicates with the Gazebo server at the default IP address http://localhost:11347, but this default address can be altered with the GAZEBO_MASTER_URI environment variable to redirect to the Gazebo simulation server.

Redirecting communication from the Gazebo server back to each robot’s backend is more complex. When a model is spawned, it automatically loads plugins defined in the robot’s URDF model. These plugins have access to the Gazebo API and can interact with the Gazebo world or model as needed. Additionally, they create a ROS node handle, enabling communication with ros_master to publish, subscribe, or call services.

In theory, each plugin would need to connect to a different ros_master instance, corresponding to the robot it belongs to. In practice, this is not possible because ROS uses a global singleton node handle, which means a single process (in this case, the Gazebo server) cannot maintain multiple connections to different ros_master instances with different ROS_MASTER_URI values. Changing the ROS master URI inside the Gazebo container would therefore affect all loaded plugins, making per-robot routing impossible. For this reason, modifying plugins to talk to different ros_master instances is not a viable solution.

As a result, communication between robots and the simulation must bypass ROS on the Gazebo side entirely. Instead, the robot backends connect directly to Gazebo using its native transport layer, subscribing to and publishing on Gazebo topics (either default ones or those advertised by Gazebo plugins). This approach keeps Gazebo as a pure simulation server and avoids the limitations imposed by ROS’s global state.

Using Gazebo transport requires including Gazebo transport libraries in the robot containers and working with Gazebo messages, which are based on Protocol Buffers rather than ROS messages. While this adds a small integration overhead, the communication model remains conceptually similar to ROS pub/sub and scales cleanly with multiple robots, each running its own independent ros_master.

Conclusion

The accompanying diagram illustrates the proposed architecture from the perspective of containers and processes. It depicts how the Docker network interconnects the containers for Robot A and Robot B, each with its own ros_master, navigation stack nodes, and rosbridge node, to the central Gazebo simulator container that houses the Gazebo server and client GUI. This setup ensures that source code and binaries are consistently shared and mounted across robot containers, while the Gazebo simulator manages the simulation environment.  Architecture of Docker containers

Architecture of Docker containers

In the following post, I will delve into the specifics of setting up the development environment and orchestrating these Docker containers, providing a step-by-step guide to replicating this architecture.