A short-lived but functional full-stack service designed to help drones automatically avoid bad weather.

Volunteering

I currently work at AT&T, and to be honest, it’s not exactly a dream job. But this post isn’t about complaining about corporate life — it’s about an opportunity that suddenly appeared out of nowhere.

My inbox gets flooded with corporate emails every day. Usually, I just skim them to see if they’re relevant, and if not, they’re gone forever. But one day I noticed a message from The Opportunity Marketplace — a place where colleagues can share project needs or ask for help with interesting internal work. The post I came across mentioned they were looking for a software expert to help with sensor data processing, computer vision, and embedded programming. All of it related to drones.

This was only one month after I joined the company. I honestly didn’t think I’d ever get to work on anything related to robotics here. After a few days, I saw that many colleagues had already applied. I quickly updated my CV — luckily it wasn’t too outdated — and applied as well. Soon after, I got a short email telling me someone would contact me. Someone did, and we exchanged a few messages. They asked me to wait while they processed applications. And then… silence. No more emails. Nothing from July to October.

At that point, I had basically forgotten that I even applied. I assumed they picked someone better or someone located closer to their offices. But then, out of nowhere, an email arrived: “Congratulations, you have been selected for …” And suddenly I was part of a drone-related project. That alone gave me a huge wave of motivation and energy.

During the first meeting, they explained that this was volunteer-based and I shouldn’t prioritize it over my day job. But they also promised that once the project officially kicked off, I could become a regular member of the team. That was incredibly motivating. I put a lot of effort into the project to show they had made a good choice.

Unfortunately, I have to mention this upfront: in April they told me the project didn’t pass its audit, didn’t receive funding, and they couldn’t ask me to continue volunteering.

I was honestly disappointed, but I still gained valuable experience. And that’s what this post is about — documenting what I worked on, including the architecture and frameworks I used.

What is GAOF

GAOF stands for Geocast Air Operations Framework, a platform for safe, secure, and reliable drone operations. It was designed by Robert J. Hall and described in this paper. In short, it’s a framework for remotely controlling drones operating Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS). It allows pilots to send commands even when the drone is far away.

GAOF also defines no-fly zones — areas that an autonomous drone must avoid, such as airports or military bases. Another group of zones is weather-related, and this is where my work came in: building a weather service that represents weather conditions as geofenced zones. For example, if there is rain in an area, the drone should avoid entering it.

Definition of the problem

The main use case for the pilot was to obtain all nearby weather zones within a defined radius that could affect the drone’s flight path. The service therefore needed to:

- Provide CRUD operations for zones

- Get weather information for a specific position

- Automatically refresh weather data for zones

- Store zones and related weather in persistent storage

- Visualize zones on a map (not required, but extremely useful for development)

Architecture and implementation overview

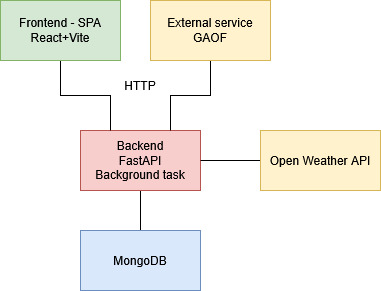

These requirements fit a typical full-stack architecture: a backend handling core logic, a frontend used as a development/debugging tool, and a database for persistent data. Only the backend interacts with GAOF.

Backend

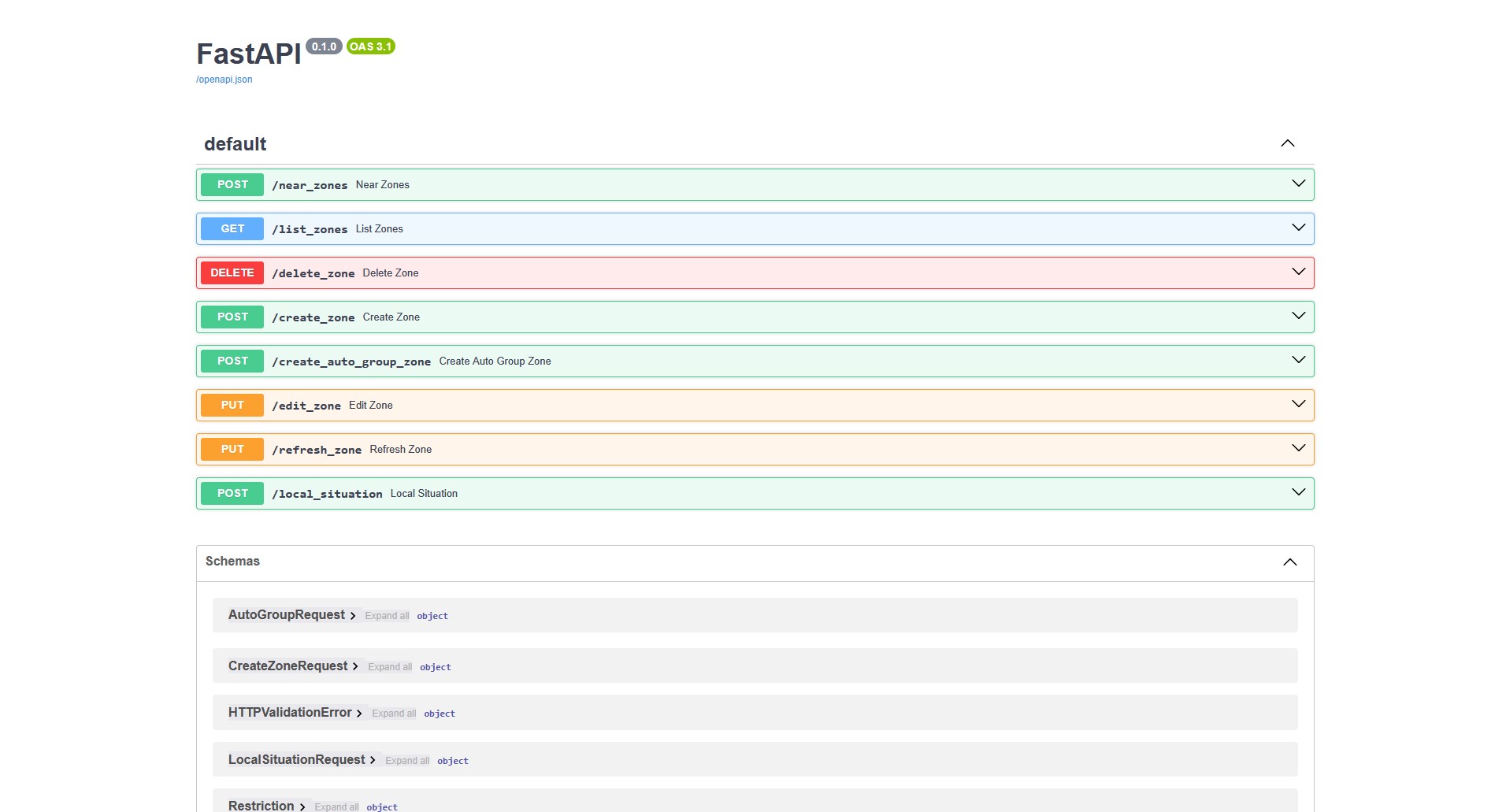

I used FastAPI for the backend — a modern Python framework for building REST APIs. The choice was obvious: I’m a Python developer, and FastAPI is well-designed for this kind of service. I could have used Flask and combined the backend and frontend into one app, but I wanted a separate frontend, and FastAPI’s async nature and Pydantic integration made it an ideal choice.

FastAPI uses Pydantic models for request/response validation, which gives type hints, schema validation, and easy JSON serialization/deserialization.

The backend responsibilities included:

- managing zones (CRUD)

- automatically generating zones in an area of interest

- keeping zone data up to date

- exposing REST APIs for frontend and external services

- fetching weather information

- encapsulating database access

API endpoints

- /near_zones — find zones within a radius of given coordinates

- /list_zones — list all zones

- /create_zone — create a zone from rectangle coordinates and type

- /edit_zone — edit a zone by ID

- /delete_zone — delete a zone by ID

- /refresh_zone — refresh weather data for a zone

- /create_auto_group_zone — create an auto-group zone

- /local_situation — create an auto-group zone for local coordinates

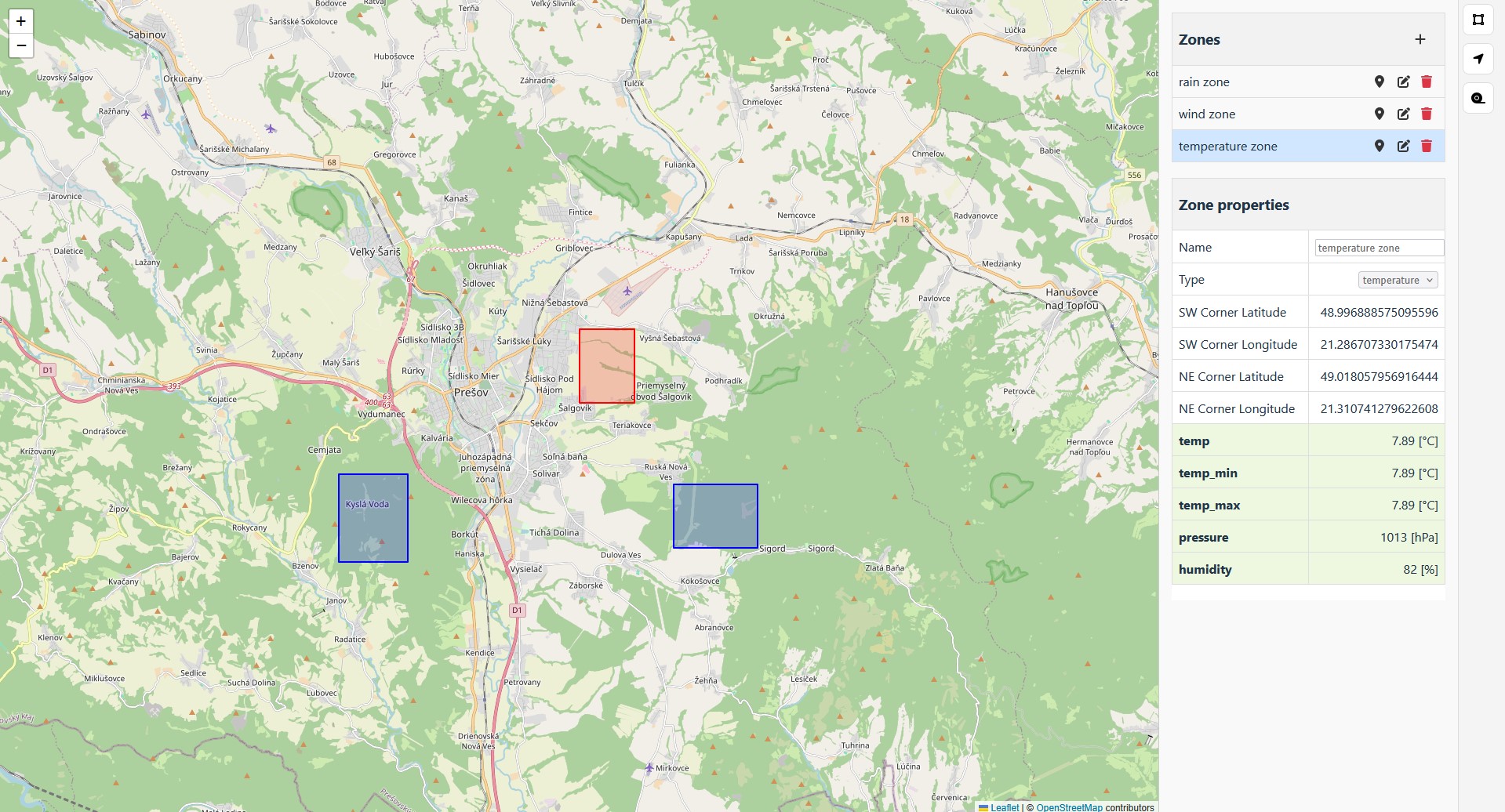

Zone

A zone is the core element in the system. It contains a name, geographic bounding box, type, and weather payload. Types include wind, rain, visibility, temperature, and auto_group.

To get both wind and rain information, the pilot must create two overlapping zones. When a drone gets near a zone, it can read the weather conditions, and if its design cannot tolerate those conditions, it must avoid the zone.

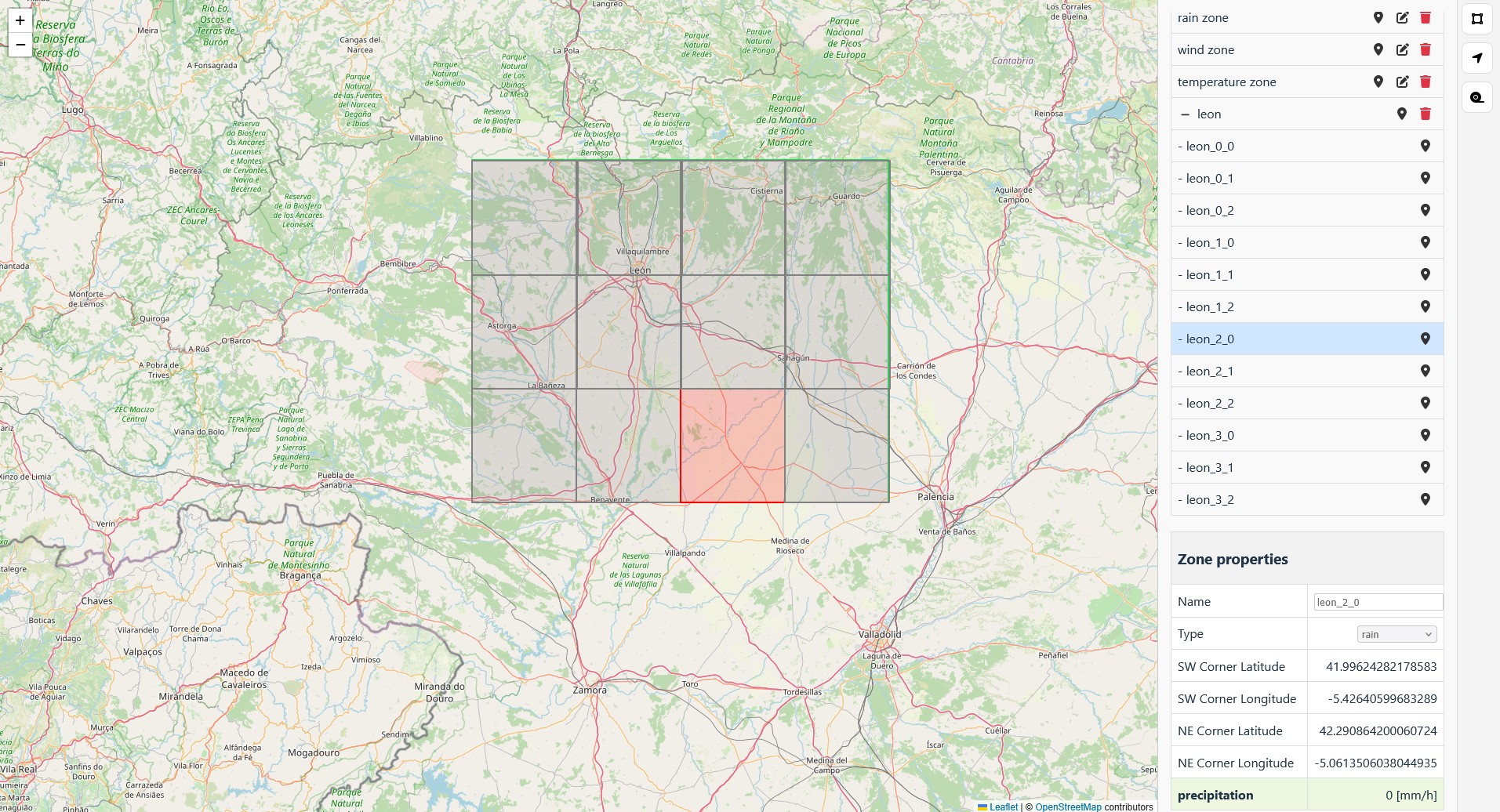

Weather is treated as uniform across the entire zone, based on the midpoint coordinate. This is too coarse for large zones, which is why I introduced the auto_group zone type.

An auto_group zone automatically generates many smaller sub-zones using a chosen resolution. Each sub-zone gets its own weather reading. When pilot request nearby zones, only active ones — those exceeding defined thresholds — are returned. In practice, an auto_group zone behaves like a pixel map of weather conditions.

Weather service

I chose the OpenWeather API mainly because it has a free tier and a simple interface. I fully expect this to change in the future, but for early development it worked well.

Background task

Most backends eventually need background jobs. In my case, it was periodic weather refresh. I kept it simple: using FastAPI’s lifespan feature, I started an asyncio task that periodically loops through zones and refreshes their weather.

Database

I used MongoDB because it is extremely easy to work with. The document-oriented structure maps nicely to Pydantic models, and MongoDB Compass makes it easy to inspect what’s happening during development.

Data model

All zones share the same structure: name, type, bounding box, active flag, and a payload. The payload structure depends on the zone type. Example for a wind zone:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

{

"_id": {

"$oid": "6931a58de878a41e14bb3cfe"

},

"name": "wind_zone",

"zone_type": "wind",

"bbox": {

"south_west": {

"lat": 48.94291101029878,

"lon": 21.162078331183253

},

"north_east": {

"lat": 48.95294466491526,

"lon": 21.174610319109277

}

},

"active": true,

"payload": {

"wind_speed": 0.57,

"wind_direction": 112

}

}

Frontend

The frontend wasn’t officially required, but I honestly can’t imagine developing this project without one. It deals directly with maps and geometric shapes, so I needed a tool to draw and visualize zones.

I’m not a strong frontend developer, but I wanted to use this as an opportunity to learn. I chose React with TypeScript, and used Vite as the tooling. The frontend is a Single Page Application (SPA), which I prefer because it cleanly separates the frontend from the backend — the frontend just fetches data, and everything else runs in the browser.

The UI consists of two main components: the map and a side panel for zone management and tools.

Map

For the map I used Leaflet with default OpenStreetMap tiles. Leaflet provides everything needed to draw rectangles, visualize zones, and even create new zones directly on the map.

Side panel

The side panel contains all zone-related actions: CRUD operations, centering the map on a selected zone, and showing zone properties for quick inspection. Later I added helpful development tools such as:

- a position marker (like a geo-bookmark with copy-to-clipboard)

- a distance measurement tool (used to calculate auto_group resolution)

Screenshots

[A map showing three weather zones]

[A map showing three weather zones]

[The auto-group zone with its sub-zones]

[The auto-group zone with its sub-zones]

[The backend API as shown in Swagger]

[The backend API as shown in Swagger]

Lessons learned

I could have added much more functionality, but as mentioned, the project was canceled. Still, I really enjoyed working on it — partly because it involved drones, and partly because I built it from scratch and understood it completely. I don’t regret any of the time I spent on it. It taught me a lot about FastAPI and frontend development, and it was fun watching it evolve.

If you want to take a look, check the project’s README. It contains all the information needed to configure and run it.